...but told my children

INTRODUCTION: FOR THE LOVE OF LORE1. KEEPING MY HEAD WHEN I ALMOST LOST MY FINGER

2. ON THE ROAD AGAIN-- AT THREE?

3. A RUDE WELCOME TO THE NEIGHBORHOOD

4. I LEARN SOME FACTS ABOUT LIFE IN THE 1st GRADE

5. WHEN I TRIED TO FLY AND FLATTENED A BULLY

7. THE DAY I ALMOST GOT A POLICE RECORD

9. YOU TOO HAVE STORIES TO TELL

10. MY 15 MINUTES OF HIGH SCHOOL FAME

11. MY 15 MINUTES OF HIGH SCHOOL INFAMY

12. SWEET REVENGE FROM UNDER THE BED

13. MOTORCYCLE MIRACLE #1: A CIRCUS ACT?

For some reason or another I have always been fascinated by the stories my parents and family have told me about their personal experiences. This is probably true with most children who are being exposed to the bigger world their elders have experienced. Later, as a parent myself and then as an elementary and a middle school teacher, I know my children and my students seemed to enjoy my stories when they served to make a point more interesting and personal than the lesson itself--which I hope was most of the time.

Two aspects of my own stories really amaze me. The first is that I have such vivid memories of experiences which happened to me at a very early age, sometimes dating back to when I was two or three years old. Many people tell me they don't remember much before kindergarten. I wonder if it's not remembering or just not taking the time to remember. We have all had experiences before kindergarten, but maybe these forgotten memories just need to be coaxed out of us. The second aspect of my recollection of my youth which really surprises me is that I not only remember the event or experience which happened to me, but I remember what I was thinking or feeling when it was happening, and how sophisticated and complex those thoughts and feelings were even at a very early age.

And so, with the encouragement of my own children and my students over thirty years of teaching and story telling, I thought to put into print some of my experiences. None of these are earthshaking in themselves, but I feel there is a certain interest there, and the telling of a few of these stories might encourage the reader to tell his/her own stories. This "cute compendium" on my take on life is written for children as well as adults of all ages.

My aim is to entertain with humor and insight, and to demonstrate and briefly discuss the art and purpose of telling about one's experiences. To this end, at various times inserted between these stories, will be short essay on the nature and importance of story telling, why we want to tell our stories, what makes a good story, and how we all have stories to tell.

Herein are some of the stories in my life starting when I was about three and continuing to I was twenty. I hope you enjoy reading my little adventures as much as I have enjoyed writing about them.

When I was three years old I must have been a pretty determined little kid. I knew I was three because we didn't move to Belmont, California until 1950. I was a babyboomer born in 1947, and this happened when I lived on Tilia Street in San Mateo near Borel School. What really surprised me about the following experience was that I felt like I was in complete control, even though my mother and her visiting friend didn't know what had to be done, and I did.

I was sitting in the dirt driveway between the back porch and the garage. I have a vague recollection of wearing a brown cap and a jacket--my mom always seemed to bundle me up before she let me go outside lest I somehow "catch a cold." Anyway, there I was, sitting there holding a one-by-four stick on the ground with my left hand while my right hand held a hatchet about head high. I was in the process of making a boat, and the intended strike of the hatchet was to help make the diagonal cut of what was to be the bow of that boat.

When the hatchet made a deep diagonal cut in my left index finger instead of the board my first thought was how stupid I had been and how my father would not be proud of my mishandling a tool. I immediately realized that this was a fairly serious accident, and I remember myself not crying, even though the cut was to the bone. I went to the back door, and tried to get my mom's attention while she was engrossed in conversation with this emaciated, chain-smoking lady friend of hers, Enis. Probably because I wasn't screaming bloody murder, it took some time for me to get her attention and tell her that I had cut my finger really badly, and that I thought she should take me to the hospital to get stitches. (I think I learned about stitches from the time I pushed my baby sister Mary and she fell on a cradle, and had to get stitches above her eye, but that's another story.)

Enis, who was more outspoken than my mother, just kind of blew off off my suggestion without even looking at my half severed finger. I distinctly remember her saying, "You don't need stitches. Just put it in a glass of salt water and vinegar to kill the germs."

I don't remember if I actually told this chain-smoking, coffee-drinking lady to her face that she didn't know what she was talking about, but I surely felt that, especially when my mom agreed with her, and did what she had recommended. I was really angry, and my finger didn't hurt as much as my feelings that my good judgment was being ignored. They thought that just because I was a little kid that I didn't know anything. Today, fifty-five years later, I have a scar which would have been smaller had it been stitched. It also reminds me to trust my own judgment, and that adults don't know all the right answers all of the time.

Since my mom didn't know how to drive a car, she took me everywhere she could walk. Consequently at the very early age of two or three I became familiar with the surrounding neighborhood. I also had a desire to travel--with or without my mother. There are two distinct occasions I vividly recall when I somehow left our house on Tilia Street in San Mateo, and ventured about on my own, either on foot, or riding my trusty tricycle.

|

My then young parents, my sister, me, and our dog Casey at our first house on Tilia Street off Borel in San Mateo, CA. 1947. |

Here I am with my grandfather, who at one point tried to curtail my exploring the city by putting my tricycle up in the garage rafters. He was strict. |

"I just came to visit you, Uncle Joe." are the only words I remember, but I was so proud of myself for having found him, and happy that he was happy too to see me. Apparently, I had quite a habit of taking off on my own, not really running away because I wasn't angry at anyone, but just exploring the territory on my own. I say this because my parents later told me that my dad's father, my paternal grandfather, was determined to keep me from flying the coop by hanging my tricycle out of my reach in the rafters of our garage.

Even drastic action of my grandfather that didn't cure my desire for travel and adventure. My longest trip by myself was on foot, taking me from where the Alameda de las Pulgas meets what is now Highway 92 down to El Camino, which was about a mile. Back then, when I was three years old, what is now Highway 92 was a narrow, winding road bordered by a cow pasture and what I now know as eucalyptus trees. I remember standing on the corner of that street and El Camino, knowing better not to cross that busy intersection, and realizing I was at the end of my journey. I stood there watching and fascinated by a bulldozer grading the ground of what was to later be a Union 76 gas station.

As I was pondering this very interesting construction project in action, I heard a car pull over, and one of bunch of girls squeal out, "Isn't that Joey Barile?" They were driving what I now know was a gray 1948 Chevy--you know, the ones which had the backside curving toward the ground. The girls stopped and scooped me into the vehicle. Like a little puppy I lapped up all the fuss they were making over me. They obviously returned me to my parents, but I don't have any recollection of that.

Looking back now, however, two questions come to mind: first, Why was I always taking off? and second, Where was my mom that she let me get away so easily? Given my past record, you'd think she'd be watching me like a hawk. I'll have to ask her the next time I see her.

My father built our own house on Chevy Street in Belmont, California, in 1950, when Belmont was a town of 5,000 inhabitants. We probably moved in when I was four or five so this was some years later, but one of my earliest recollections of exploring the neighborhood was when my three year old sister and I were walking down a dirt covered road called Clee Street. Apparently it had rained because there were huge puddles all over the street. That's where I first met a towheaded roly-poly little kid who gave me a welcoming party of his own. I don't know exactly what happened, but my sister was mouthing off to this kid, whose name was Pitt. As little kids often do, she taunted him totally unaware of the consequences. Pitt didn't say a word, but pushed her into a mud puddle which was about her full length. She was all tears, and looking at me as if to say, "Are you, my flesh and blood brother, going to allow that?"

|

Even though I was glad someone had stood up to her and taught her a lesson, I surprised myself by defending her. "You can't do that," I yelled, trying to sound menacing, but before I could say more I too was thrown into the puddle right next to her. |

Meanwhile, I was proud of myself, and somewhat surprised at my newfound courage, for having defended my sister. Blood was indeed thicker than water...and mud.

4. I LEARN SOME FACTS ABOUT LIFE IN THE 1st

GRADE

When I was in the first grade at Louis Barrett School two memorable events happened to me which introduced me to some of the brutality and kindness in the world.

The first occurred when I was watching a fourth grade girls' kickball game and the second experience began in a pine tree high above the playing field. First, imagine seeing this little kid wearing glasses and standing on second base in the middle of a kickball game. Yep, that was me, and I was having fun watching these big kids play some sort of game. I could clearly see all the action because I was standing in a square which I later learned was second base. Wow, I thought, these fourth grade girls were big, but then just about everyone is bigger than you if you're in the first grade. So there I stood, looking through my glasses with silent amazement at the game before me. It seemed perfectly natural because no one had ever told me to move. Suddenly, out of the blue and for no apparent reason at all and without any warning whatsoever, this really large fourth grade girl plowed into me, knocking me off my feet, and shattering my non-shatterproof glasses.

|

I was hurt and really frightened at having my glasses broken, and I wasn't embarrassed to cry in front of the whole play ground. Some kids took me to the principal's office, and a very nice man talked to me and made me feel much better. I never forgot his kindness and concern for me. Later I was to find out that he was the school's principal, and that his name was Mr. Battistini. The real coincidence would be that nineteen or twenty years later, I would stand before this very same individual and interview for a teaching position in the Belmont School District. I don't think I made the connection then, but I will have to send him a copy of this story, and thank him again for the kindness he showed me some fifty years ago. |

|

My next encounter involved a tree, a word, and my mother. I was six years old, and had just climbed to the top of a twenty foot pine tree overlooking Louis Barrett School. At this height I discovered a word which I had never seen before carved into a debarked square. It was a four letter word beginning with an S and ending with a T, and I quickly used my newly learned phonics skills to sound out this strange looking new work. Then, I scampered down the tree, and headed home to ask my mom what this word meant. Apparently I had sounded it out correctly because she knew what it meant, and was angry with me for repeating such an awful word. It wasn't my fault I told her: I found it in a tree. I didn't even know what the word meant, but I was still proud of myself for sounding out a word all by myself. I was also surprised that there were such things as bad words, because in those days kids our age were really sheltered. At least I was. Yet I was amazed how some words had a secret power to make some people angry.

About five years later when I was about ten years old, Pitt and I were playing in a vacant lot across from his house on Clee Street. There were all sorts of other neighbor kids there also, but the Cirimele's house had not yet been built, and the lot was a great place to play. There I sat on my haunches eight feet up in an oak tree where I surveyed all the activity below. I was wearing my Zorro cape, which was an old sheet I borrowed from my mom. I was a very curious child, and there up in that tree I was pondering the possibility of my floating down from my eight foot high perch if I held the corners of my cape and made it into some sort of parachute.

Nevertheless, I had my doubts whether this cape used as an experimental parachute would work, and so I needed a backup plan. And then the answer to my prayer appeared. Right below me stood Pitt who apparently wasn't aware that I was right above him plotting an experiment. He was still kind of chubby, and seemed like a soft object to land on should my experiment fail. I seized the moment and I jumped.

To my surprise I came down like a ton of bricks, but according to my plan I landed right on top of Pitt. He was a lot softer than the hard ground. I started congratulating myself for thinking so far ahead. Meanwhile, Pitt didn't know what had hit him. He was hurt and crying. I saw him look at me and figure out that I was somehow responsible for his pain, and then, to my horror, I saw his hurt turn to anger. The tears seem to evaporate from his reddened cheeks. I could see the hatred in his eyes, realized that this hadn't been such a good idea after all, and I knew I had to do something fast.

|

In one of the greatest moves in my whole life, even to this day, I utterly surprised myself as I yelled out the following lie. "Pitt, you saved my life; I fell out of this tree, and you broke my fall. I could have broken my neck." To my surprise he was buying it. I continued pouring it on. "There must be some reward in this for you. My mother will be so thankful. Hey, you guys, did you see what Pitt did?" |

Jimmy's mom always pampered him, and he was probably the most spoiled kid in the neighborhood. His parents were really fantastic, and treated me very nicely, but they gave him everything he ever asked for, and always asked him what he wanted. Furthermore, he always seemed to want more and was often complaining or whining. His mom even cut the crust off the sandwiches she would make him.

Even though he was a pretty spoiled kid, I palled around with him, and I tolerated some of his tantrums maybe because I was older and he liked me, and maybe because I liked his mom. Mrs.Worrell was always was so nice to me, and made me feel special. She was pretty, and always had a nice smile for me. Now that I think about it, I suppose I had a crush on her. For her part, I think she was desperate for her Jimmy to have a friend, and she liked the fact that I was good to him, and respectful to her. Besides Jimmy had a lot of interesting toys to play with, and his mom let us watch television, especially The Mickey Mouse Club with "The Adventures of Spin and Marty." I didn't have that many toys of my own, came from a large family, and wasn't not allowed to watch television when I could "go outside and play" instead. But watching tons of television, especially cartoons, made for Jimmy's downfall in many instances, especially the one I'm about to tell you about.

Despite his being spoiled, Jimmy was still a pretty smart kid. I was really impressed the day he put on a magic show (probably with the organizational help from his parents who managed to round up all the kids in the neighborhood). Including parents, there must have been fifty to seventy-five people sitting in chairs and on the lawn in his backyard as Jimmy performed trick after trick.

It just so happened that Pitt, the neighborhood bully and next-door neighbor to Jimmy, was in the audience. He was commenting and heckling every trick Jimmy tried, but Jimmy seemed to keep his professional cool, politely ignoring Pitt and his criticisms.

When Jimmy asked for a volunteer, it was Pitt who jumped forward. Jimmy pulled out a table cloth and showed both sides. This looked strangely familiar to a cartoon we had both seen. Then it was clear: this was a reenactment of the cartoon where Popeye draped the magic cloth over Bluto and slugs him in the face showing Bluto now with a glaring black eye. I couldn't believe Jimmy would do this. This was not a cartoon; it's real life. Surely he wouldn't do this in front of all those kids and parents to the biggest, meanest kid in the neighborhood. Jimmy wouldn't be so brazen, I flashed.

Jimmy put the table cloth over the head of a smirking heckler. He then stepped back, made a fist, and hit the lump under the shroud with all his might. Not losing a beat, he then pulled off the sheet to reveal the once smug and smirking heckler immediately transformed to a hurt, crying, and red-faced baby. Pitt really looked foolish, and it took him a few seconds to figure our whether he was more hurt, more embarrassed, or more angry. Anger won out, and he jumped up and chased Jimmy out of his backyard and around the neighborhood.

The audience sat shocked. It had happened so fast, but gradually it dawned on us what had really happened, and we laughed and cheered Jimmy as he ran for his life. Jimmy, the kid who watched too many cartoons, had either flipped out, confusing reality with fantasy, or had just summoned the courage to do something we had always wanted to do. That day, my admiration for Jimmy reached a new height. Also, from that day forward, for whatever the reason, Pitt stopped being the neighborhood bully. He actually turned out to be a pretty nice guy, was pretty popular, and has turned into one of my life-long friends. I'm sure no one present that summer day in 1956 will ever forget that harrowing and transformative incident.

I was probably at that age, 12 to 13, when I was trying to live a little on the wild side, or at least appear to my friends that I was not a goodie-goodie or a mamma's boy--something every guy coming of age had to prove to himself and his friends. Up to this time I was a pretty innocent kid, never trying to get into any trouble, break any rules, and certainly not run into trouble with the police. Things I had done up to then might have been illegal, but I was not aware of it, nor was I intentionally breaking the law to be cool or show-off for my friends. I was a pretty good kid.

Well, as my father used to say, some of the worst things kids do take place when one comes under the influence of the all powerful crowd of one's friends. Such was the case with me when the group challenged me to get my BB gun and go hunting with them in the Frigoli's lot, which was on the hillside of Ralston Avenue.

Wanting to be one of the guys, I went to my bedroom, and stuck the rifle down my pants leg, and snuck out of the house. The rule was that the BB gun was to be used in the backyard, and now to fit in I was breaking one of the rules I had agreed upon with my dad.

"Joe, why are you limping?" my mother called to me as I was stiff legging it down the driveway.

"Oh, I just hurt my leg. It's nothing," I lied. Boy, I thought, first I'm going against my parents'wishes, and now I'm lying to my mom. This thing is really getting complicated.... Well, there's no going back now.

The next scene is five of us in the lot shooting at birds, laughing, and making all sorts of noise and wisecracks. The birds didn't stick around very long, and were soon in the adjacent lot. The guys just followed the birds, and I somewhat reluctantly followed them trespassing on someone else's property. I wasn't too keen on this idea, and I moved to the back of the lot, somewhat suspicious that the neighbors would notice all the racket and phone the police. I was getting very nervous, and was all ears.

Then I heard it, the not too distant crackling of a microphone, the kind that the police use on a two-wave radio. My eyes searched the front of the lot by the back of the house. And then I saw the movement of at least two men in blue--Belmont police officers.

I shouted a whispered warning to my friends, "Hey you guys: the cops."

No sooner than I had said this a voice sounded over a microphone,"All right, you kids, come on out. This is the police."

The last thing I wanted was to be caught by the police and be reported to my parents as a promise breaker, a sneak, a liar, and a trespasser. It would be too embarrassing to get caught, exposed, and have a police record. I ran, and the rest of the kids, encouraged by my move, followed.

Holding my rifle in one hand, I crashed through brush, splashed through a shallow creek, and scaled the steep back heading up toward Chula Vista. My fear propelled me like a jackrabbit, and the sight of me scurrying up a steep hill, gravel propelled from behind my tennis shoes, and my jumping over bushes as fast as I could go must have seemed a very funny sight because I heard one of the guys behind me laugh and say, "Hey, look at Barile; he's running like a rabbit." It didn't seem like the police were following on foot, so the last thing I did was to stash the BB gun in a bush which I mentally marked so I could pick it up later that night. I continued to run.

I never even looked back. I reached Chula Vista, took a right, and headed toward Carlmont High School. Somewhere I heard a distance siren, and my overactive imagination reasoned that the Belmont police force was radioing ahead to catch us a we ran across town. By now I didn't hear my friends behind me, but I kept running until I reached the top of Motorcycle Hill behind Carlmont. From there I ran across Ralston Middle School, and down Ralston Avenue and all the way up Alameda de las Pulgas. I finally ended up at my aunt's house on Lyons Avenue, at the far side of the city. I had run without stopping about three miles, and none of my pursuers, real or imagined, were anywhere in sight.

I arrived, greatly relieved, at my Aunt Nellie's front door. Thank god she was home. She was pleasantly surprised to see me, and to her question of "Joey, what are you doing here?" I answered, "I just thought I'd stop by and visit you, Aunt Nellie." This lie didn't seem as bad, probably because I really did like my aunt and my two cousins, two girls who were about my age. More importantly at that moment, her house was to me a safe haven from the police, who no doubt were combing the city for the young marauders who dared to disobey a direct command to stop.

After a few hours of hiding out, and fortified with milk and cookies, I cautiously and casually started walking back to where I had left my BB gun. It was getting dark, and I wondered if I would be able to find it. I hoped it wouldn't be all covered with dew, but that could be wiped off and oiled so the gun would not rust. I went the back way via Escondido Street, and up the creek from there. No use calling attention to myself by walking through the front entrance of the scene of the crime.

Boy, I prayed as I walked through the woods, "if I could just find my gun and get home safely, I promise I would never again do anything so stupid." Well, I did find the rifle, I was able to sneak it back into my bedroom, and I, for the most part, kept my promise. I had learned my lesson, and was thankful that I somehow got through it all without anyone else having to know. Never again would I consciously break the law. It wasn't worth it. And other than a few traffic violations, I never did. I'll never forget that day when I almost got a police record.

In spite of all the experiences I have had, these were nothing compared to those of some of the kids in our neighborhood. I never had a broken bone, never had a police record, didn't get into trouble at school, had pretty good grades, and had relatively few scars on my body. On the other hand, the kids across the street were another story completely: all four boys were downright reckless. The following story will illustrate how crazy they were.

The action took place on a huge twenty-foot-long rope swing which hung from the thick branch of a bay tree, some ten or fifteen feet above the creek which ran next to Ralston Avenue. I was a spectator. I saw three brothers at one time involved with the rope swing: Jimmy was on the bottom swinging over the creek. Ten feet above Jimmy, hanging on to a knot on the same rope was Jerry. Meanwhile, above both of his brothers, was Kevin, who was on the branch where the rope had been tied. For some weird and unexplained reason Kevin seemed to be trying to untie the knot. I guess he thought it would be funny to see his brothers fall into the creek below. Anyway, as he us probably another fifteen to twenty feet above them, and looking down at them at a strange angle, he was probably over come with motion sickness. He got sick and threw up.

Whether he aimed or not, I do not know, but the vomit struck the middle brother, Jerry, on the shoulder. Jerry took a quick look at what hit him and probably got a good smell too. His immediate reaction was to also toss his cookies (and this was anything but cookies). As if perfectly timed, this projected barf hit Jimmy below who also got sick. So there they were, three brothers lined up above one another, puking up their morning breakfast on each other. The timing was incredible, the view was very funny, especially is you were a bystander of this unusual circus act. It was one of the greatest spontaneous shows I had ever witnessed. This was one of the weirder things which ever happened in our neighborhood.

As I write this now all three brother have died: one by suicide, the other in a motorcycle accident, and the third just recently of a heart attack. How or what made these brothers behave the way they did could be a case study in itself, but I'm just reporting the facts as I saw them.

A friend of mine who is really a rocket scientist and a mathematician once remarked to me that "every number in our counting system has some interesting component about it." Zero is unique and special for many reasons: multiplying by it reduces any other number to zero. Adding zero to any number does not increase or diminish the value of that number. The number one is unique in that when you multiply a number by it, the product is that number itself. Two is the first even number, and the first and only even number which is a prime number. And so on and so forth: every number is "interesting" in the sense that it is unique and special in one way or another if you know what to look for.

Likewise and even more so, every person is unique and special, and has an interesting life, and interesting stories to tell, especially if you know what to look for. Sure, there are some exceptional people who have had exceptional experiences, and even exceptional lives, who really have exceptional stories to tell. These people are oftentimes famous. The lives of these famous people are oftentimes so busy that they may not have had the time, or taken the time, to write about themselves and their experiences. Others (biographers, reporters, etc.) have done this on their behalf, trying to piece together what they were thinking or feeling while on the road to becoming famous. Nevertheless, even those of us who are less famous (and Andy Warhol said we all have 15 minutes of fame), we all have some unique and interesting stories to tell for several reasons.

And what are some of the which reasons that make our stories interesting to others? First, the uniqueness of the experience itself might provoke interest. It may be exceptionally funny, or frightening, in itself. Second, what we think and feel about the experience, either as it's unfolding or afterwards, and our reactions to it might even be more insightful or perceptive than the happening itself. For example, my thoughts and feelings as a three-year-old when I just about cut off my finger are really interesting because I didn't think a little kid could have such thoughts and feelings. Third, the way we tell the story--the use of descriptive vocabulary, the enthusiasm we convey by our voice and/or sentence structure, and pace at which we relate the information, speeding up or slowing down when effective--all of these story telling techniques and more are called the style or the way in which we tell the story. In summary, the three parts to making a story interesting are: the story itself should have some value in itself; our feelings and thoughts about the story are an important part of the story; and finally, the way we tell it, the style we use. With a little practice, anyone can learn to tell a good story.

These are my conclusions after 30 years of teaching middle school students, and raising two children of my own. Telling a story often worked well to make a point about something we were talking about. Or sometimes just to recapture interest when the teaching started getting boring. A well placed personal story often breaks down the distance sometimes felt between a teacher and students. It can often bond the story teller and the listener, giving insight and understanding into the story teller, which is personally revealing, and puts us all on equal footing with each other. By showing myself as a real person with childlike thoughts, fears, and weaknesses I reestablish myself as a real and credible person, who isn't too unlike them. It lets them know it's okay to be a kid.

I attended high school at St. Joseph's, a small boarding school in Los Altos. It was made up of a high school and two years of college, and was technically called St. Joseph's College. There were only 600 students in the whole school, about one hundred per grade level. We were very self-contained and isolated from other schools. Our sports program was an intramural program, which meant that we just had teams within the high school portion, and that we played against ourselves, and not against other schools. The teams were the Indians, the Bears, the Trojans, and the Ramblers, and the rivalry between these teams stemmed from when the school was first constructed in 1924.

When I entered as a freshman I was chosen to be an Indian. So all year long we would play against the other teams in all sports, and at the end of the year the team with the most points would take the year as the best team. There were no trophies, or even records that I know about, but it was really a big thing to win a sport, and especially to win recognition for the whole year.

I soon discovered that all my running around the neighborhood back home--playing tag, jumping over hedges, and, in some cases, some small parked cars--all of this activity had built up my legs. I found that I was a pretty good high jumper. I never had any training, but I simply hurdled over the bar, not using the traditional Western Roll or the newly discovered Fossbury flop or the scissors method. Our team captain was a junior in high school, and we never had a Physical Education program or any sort of formal coaching. It was just older teammates teaching younger ones.

|

|

As a freshman I was small enough to be on the Peanut Division of my team, the Indians. My moment of glory came at the high jump event. As predicted, I took first place, but then the real challenge was to beat a 1929 record for the Peanut Division which was four feet and ten inches. I was about five foot three inches so the bar which I was trying to clear was set at four feet and eleven inches, the height of my eyes as I looked at it. |

Much of school turned out for the event, to see the kid with the weird way of jumping try to break the record. I was to have three attempts to complete the jump. I walked up to the bar, and paced my way back, figuring where I would push off with my left foot, and how far I had to run to get up enough speed for maximum liftoff. I would approached the bar in an S shape so I would end up favoring my left leg from which I would push off. It was really a very unusual style, but fairly effective for me at that time.

Several hundred students seemed to surround the pit as I took off on my first attempt. I felt pumped up with all the support I was getting to break the record, and I felt great by having already taken first place. I pushed off, I went airborne, lifted by muscle, adrenaline, skill, technique, and determination. Ninety-five percent of my body was over the bar, but at the last second, my left foot caught the bar, and the bar and I crashed in the sawdust pit. I could hear the crowd let out of grown of disappointment. I dusted myself off, reset the bar, and measured again my approach.

My second attempt had the same expectation, but turned out the same way. By then I felt my legs were getting a little rubbery. The crowd started cheering me on, and I knew that this last jump was all or nothing. I didn't feel the least bit nervous, but that I was doing something more important for myself--I was jumping for the crowd. Later, a photograph would tell the story so much. It showed me in the air, twenty or thirty spectators in the background kicking their legs up as if they were jumping.

As I revved up for my third and final attempt, I said a little prayer not so much for myself but for those who came to watch, cheer me on, and possibly witness a little part of history being made. As I went down the runway, I seemed to glide. My strides seemed just long enough to propel me upward when the time came; my forward speed seemed optimum. As I jump and my spirit soared I was conscious of every part of my body as I flew over that bar, and at the split second kicked up my lagging left foot as I soared high and clear, and the silence exploded into cheers of victory and congratulations. I made it.

That night and for several weeks to come classmates and upper-class mates would congratulate me in the halls and even send me their desserts at the evening meal in the refectory. It felt nice to be a hero, but I realized that I had more than myself to thank. Four years later, even though I could almost hurdle my height, the competition would be greater, and my lack of a more efficient technique would be noticeable. Nevertheless, I'll never forget that day and those times in 1961.

The next incident I find interesting for several reasons. "Why did I do it?" to this day I ask myself. Not that what I did was any crime, but it called unfavorable attention to myself. "Was I that attention starved that I had to do something outlandish to get attention?" I don't remember whether or not this had happened before or after my high jump record bid? Probably after, when I was a sophomore in high school. And we all know that sophomore means "wise fool"in Greek.

Saint Joseph's Seminary was, as I mentioned before, a combination high school and two year college nestled in the Los Altos hills near Highway 280 which was under construction at that time. The building was shaped like a square, three or four stories high with a courtyard in the middle. It was built by the archdiocese of San Francisco as a seminary to educate young men, starting in high school, to become Roman Catholic priests. At that time I thought my vocation was to become a priest.

But basically I was, we all were, just boys with a noble and worthy dream, but we were above all else boys, not too different from other teenagers in our generation, or for that matter, teenagers in any generation. Sometimes we did off-the-wall things to prove to ourselves and others that we weren't any different than anyone else. I think that what I did back then was just such a statement.

It happened in one of our two refectories, where we had our meals. Each refectory seated about 300 students. The faculty sat at an elevated section at a long table which could seat twelve to fifteen people. We students sat below in tables which held nine. At this particular time of the year which was Lent, a time of penance, prayer, and sacrifice in preparation for Easter, we would have our meals in silence. We had all sorts of hand signals to communicate which foods we would want passed, some of which were pretty outrageous. At any meal there would be one table which was scheduled to wait on the others, passing out food, and collecting the dishes at the end of the meal. It was at one of these silent meals at the collection of plates and utensils that I, for some strange reason, started stacking plates at one table. These would eventually be placed on a huge cart which would then be wheeled into the kitchen where the Sisters of the Little Family, who did our meals and laundry, would wash them. So there I was stacking these plates, eight, twelve--one foot high, then two, and almost three, making a sort of mini tower on a table. They seemed to balance fine so I kept stacking. I don't know what I was thinking. Suddenly the quiet of the hall was shattered by the repeated ringing of a bell by one of the professors at the head table.

He shouted at me, "What do you think your doing? Take those plates down!"

The refectory exploded in laughter when they all were aware of my infamous tower. I don't recall if I was surprised, but I was definitely embarrassed at the scolding I had received and all the unwanted attention. Whether it was unwanted or not, I do not know to this day, and this action remains one of the most unexplained deeds in my life. Had I been that desperate for attention and recognition, or was I so in need of having others look at me as a class clown that I would do some of these crazy things. I wondered then. I even wonder now.

I have a love-hate relationship with scary movies: I love to watch them but I hate the scary parts. One way I could watch but not to see too much would be to put my hands up over my eyes but look through the cracks in my fingers. I started doing this and continue to do it even to this day.

I was probably about eighteen, I was in the darkened recreation hall below our college rooms at the boarding school I attended. There in the dark forty to fifty of us college freshman or sophomores were watching a horror film called The Haunting. I was sitting in the back with my hands over my eyes as the music indicated that something scary was about to happen. Just as the music reached a crescendo, one of my buddies, Peter Anderson, shouted and grabbed me from behind. I let out this embarrassing scream, and jumped two feet out of my chair. Everyone in the room burst out laughing at me, and I exited the room to hide my embarrassment and avoid any more teasing from my classmates. I promised myself that I would get even as I hurried upstairs to my room.

|

Once ensconced in the safety of my room my plan to punish my tormentor came to me quickly. Since we each had separate rooms and we were not to be in the room of another student, this was the perfect prerequisite for surprise. So before Peter came up to his room, I let myself in, and slid under his bed. There I lay waiting for about ten minutes for him to enter returning from evening prayer service which I had skipped. |

|

I finally heard him enter the room, close the door, and proceed to gargle and brush his teeth. All these personal noises made me feel that I was invading his privacy, and I almost felt guilty. Then the sounds of undressing, dropping his shoes, and his sliding under the covers. He tossed and turned inches above me, and then things were quiet. I gently tugged the sheet. He must have sat up suddenly wondering if it were just his imagination. I saw one foot hit the floor. I didn't want to be discovered and lose my element of surprise, so without anymore thought I reached out and grabbed his bare ankle. It was torn from my grip as he let out this bloodcurdling scream, and started jumping around the room in some sort of fearful dance. To prevent myself from being bludgeoned to death with some unseen weapon, I yelled, "Surprise, Pete, it's me, your old friend."

He pulled the mattress off the bed as a group of guys assembled at his door to see what was the matter. In the face of so many witnesses, the only cool thing for him to do was to laugh. Which he did, a little nervous laugh, as his shattered mind put together what had really happened.

"I'll get back at you, Barile," he promised as he pretended to have fully recovered.

And so, it was no surprise that within twenty-four hours I would find my medicine cabinet filled solid in shaving cream. We both knew, however, who had had the best and the last laugh. It's something neither of us will ever forget.

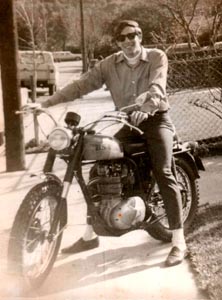

I almost died when I was twenty. I had planned to meet some of my college friends in San Francisco and play golf at Lincoln Golf Course, but mother would not let me use the family car. Not to be deterred, I told her I'd take my motorcycle which I had purchased the week before. I'd show her, I thought, as I strapped my golf clubs across the back seat of the BSA 441, and roared down Clee Street, away from my home in Belmont.

This motorcycle was a combination street and

dirt bike. It was pretty fast, able to go from zero to sixty in six

seconds. Little did I know that many, if not most, accidents on

motorcycles happened within the first week or two of purchase because

of the rider's inexperience. San Francisco was 30 miles away, and its

traffic was much more crowded than the traffic in Belmont. I was

angry at not getting the car, and I looked at going to the city as

adventure. So off I went, not concerned with my mother's feelings nor

the least bit worried about myself.

|

Thirty minutes later I was on Highway 101 near Third Avenue exit by what was Candlestick Park in San Francisco. I then heard and felt the engine sputter and die as it ran out of gas. In my impulsive departure I had forgot to check the gas tank. I cursed my stupidity as I took it out of gear and coasted to the side of the road. Fortunately, I remembered that if I leaned the bike to its side, the gas in the reserve section of the gas tank would spill out and allow me to go a little farther. It worked, and I restarted the bike, and went to a gas station along Third Avenue. |

|

Seventy-five cents filled the three gallon tank, and I was ready to get on the road again, but the traffic was heavy. I couldn't see an opening to merge back into traffic. I waited. And waited. I was already going to be late, and I was getting impatient again. Finally, I thought I saw a little space in the cross traffic so I revved the throttle and popped the clutch. The bike almost shot out from under me as it leaped into the traffic. I slid back on the seat, and was hanging on to the handlebars which controlled the gas and the clutch. The bike was lifted up on its back wheel. Somehow I stayed in the saddle, but now I couldn't steer because the front wheel was off the ground. The gas seemed to be jammed open, but it was me holding the throttle full open. The building across the street seemed to move toward me (not me towards it as was the case), and I had a sickening vision of my bike hitting the eight inch curb and getting catapulted through the huge plate glass windows of that building. In the middle of all this my mind thought how sad my mom would be at my dying. Somehow I missed the cross-traffic, and hit the curb at such an angle that it both slowed the bike and turned it so that now I was on the sidewalk.

The runaway bike continued to pull me along the sidewalk, and all I could see as I desperately hung on were the dark faces and white teeth and eyes of black people jumping out of the way of my vehicle. It never occurred to me to pull in the clutch and hit the back break. I felt a searing pain as my left foot hit the nipple of a fire hydrant. It felt like I broke all the bones in my foot. Not wanting to get trapped on the sidewalk by parked cars, I somehow managed to make a left ninety degree turn, a physical impossibility, back onto the street. Then I made another impossible right turn so I was going with the traffic. Not wanting to fall and get my legs pinned under a motorcycle, I stood on the seat for a second or two. Then I saw cross traffic ahead of me. Instinctively, I executed another impossible right turn into a parking lot where the side of a black Cadillac seemed to approach me as the front wheel of my cycle slammed into its right front tire. The impact made me do a handstand, which cut the engine, and my helmeted head kissed the hood of the parked car.

I fell back on the seat, the front wheel and forks of my motorcycle were smashed forward, and a crowd of fifty to seventy black kids came running over. Amid all the confusion, I heard the voice of some little kid yell out, "Hey, man, that was cool. Do it again!"

I slowly got off the bike, felt my ankle for broken bones which there were none, and walked over to the parking lot attendant's office. There I phoned my mom who sent my sister to pick me up. I also wrote a check to the attendant for twenty-five dollars to pay for the strip of chrome I had knocked off the car I hit. I was happy to be alive, and definitely did not enjoy having been the main attraction in my out of control ride through a busy street in San Francisco. It was there and then that I realized that I too could die, and that by some strange stroke of luck or miracle I had managed to avoid likely injury and possible death.

14. MOTORCYCLE MIRACLE #2: ALMOST BEHEADED

I really cannot remember whether my next traumatic encounter with my motorcycle took place before or after my San Francisco experience, but it was also soon after purchasing the machine. I was at Saint Joseph's, probably in my sophomore year of college. My friend at the time, Howard Baker, who later became a motorcycle cop in Redwood City, had just purchased a Honda 350, and so we were eager to ride them in the surrounding countryside.

It was in the evening when we opened a wire gate to a country road. The sun was getting low. Both Howard and I were experimenting on our new bikes, jumping the little bumps in the dirt road while going at various speeds. After about twenty minutes we decided to take the same road back and exit through the same gate.

Howard had gone ahead of me, and had stopped ahead of me while I was still driving along at about 35 miles per hour jumping little high points in the road. The light was right in my face and I did not see that he had already reached the gate which was closed. I thought I'd just speed by him when I noticed that he was waving his hands as I was about twenty feet away. In a second it occurred to me that he was trying to tell me to stop. I saw the six foot high wire mesh fence which was topped with three strands of barbed wire, and had a quick image of myself getting my head cutoff as I went through that wire at 35 mph.

I knew I was going to hit it head-on even as I hit my breaks. My back wheel locked up, skidded for ten feet, and then the front end hit and buried itself in the fence at about twenty miles per hour. My arms stiffened on the handlebars, and I was thrown over the handlebars and the fence, landing on my feet in a sitting position. The impact made me think I broke both ankles, but I could walk so that was ruled out. I felt some stinging on my shins, and when I looked down I saw that both pant legs from my knees down were shredded and that I had several long scratches on my legs where the barbed wire had lightly touched. I couldn't believe it; I was barely scratched. It could have been much worse.

The result of these two experiences on a motorcycle made me into a very careful rider. I rode that bike for a few years more, but rode it as carefully as a little old lady. Still, when riding to Bowditch Middle School in Foster City where I was doing my student teaching, people in automobiles often wouldn't see me, and accidentally drive me off the road or into a curb. Also, the buildup of oil in the center of a lane always threatened to lay down a bike and make the driver a projectile at 60 miles per hour. But it wasn't until my wife started working as a nurse in the Intensive Care Unit at Peninsula Hospital in Burlingame that I really started to realize just how dangerous riding a motorcycle was, especially in traffic. She would come home crying, saying how she saw some young man brought in with his brains hanging out because of motorcycle accident. Or how another guy was completely paralyzed from the neck down, and would be eating the rest of his meals through a straw. About the fourth day of this I decided that my life wasn't worth the gamble, and I sold the bike. Now I can only look back and think how lucky I had been to have survived my stupidity.

People have told their stories since humans began to communicate. Stories are our life's lessons shared. The young can benefit from the experience of their elders. As mentioned before, there is a sort of communion, a coming together, a bonding in the sharing of stories. The telling of a personal story often helps break down the barriers between student and teacher, young and old, male and female. Telling one's stories helps define oneself to others and to oneself. Our experiences make us who we are, and in the telling we reflect on our experiences, and benefit from that reflection. We also tell our stories to perpetuate ourselves, and our memory. We tell stories to be remembered, to be thought well of, and to be kept alive, even after we have gone. Our stories help us transcend death. Our stories keep us forever young.

Why, I wonder, are most of my stories about myself as a young person? Upon a little reflection it seems fairly obvious: I have spent most of my life dealing with young people. And so the stories I tell should have something in common with them, or at least be about something to which we can both relate. But there is more. The life of a young person is interesting because he or she is always experimenting, learning, failing, and growing. Youth are always trying new things, testing their limits, making more mistakes, and so on. Also, it's easier to talk about my mistakes now that they are well behind me. I've learned from them. They're not as embarrassing. I can laugh at myself now that I'm older. For whatever reason I have shared my experiences, I am thankful to the thousands of school children, as well as my own two children, who have endured and encouraged me to tell about my life, especially my life as a young child and teen. Children have kept me young; and I hope I have helped them on their journey to growing up, but never growing old in spirit. May we all remember and celebrate with the poet Ralph Waldo Emerson that "The child is the father of the man."

Let us remember that we all have interesting experiences, and stories to tell. I hope my stories make you more reflective on your life experiences and the lessons learned from them. May my little stories told here encourage you to remember and recount your stories. I also agree with Socrates that "the unexamined life isn't worth living." To which I might add that the experiences of one's life, if untold, aren't worth examining. In the telling we truly revisit and examine our lives, and in doing this we truly live our lives to the fullest.